“The day he was released from Bergen-Belsen was a Friday, it was close to the start of Shabbat and it was four years since my grandfather had been able to celebrate it.” Elie Lowy, grandson of Rav Dov Izhak Freilich, is betrayed by emotion as he tells of the moment of regained freedom and the moment when his grandfather was able to start living as a Jew again.

We went to New York, and there to his son, Avi Freilich, and his grandson Elie, to hear the story of this rabbi, a story that is intertwined with that of the Jewish community of Rome.

Rav Freilich was born in Kozienice, one of the Hasidic cities of Poland. At the age of 12, he moved with his family to Warsaw where he studied at the rabbinical college of Rav Kalonymus Kalman Shapira, known for having been the rabbi of a synagogue in the Warsaw ghetto. The bond between the two was very strong as Elie tells us: “My grandfather often went to Rav Shapira’s house. Theirs was a special relationship. For example, it was he who took first taste of the Shabbat food and he often told me that one night he felt his bed move. Rav Shapira had done it so that the moonlight wouldn’t touch his face. According to the Torah, the moon must not shine on any face. Rav Shapira was very protective and wanted the Torah to be comprehensible to anyone, so he often used poetic language. According to my grandfather he was one of the most modern of rabbis, he said that there are no bad children, but children who must be given direction. Everyone must be oriented according to his talent”. Rav Shapira was a point of reference, a spiritual and life guide.

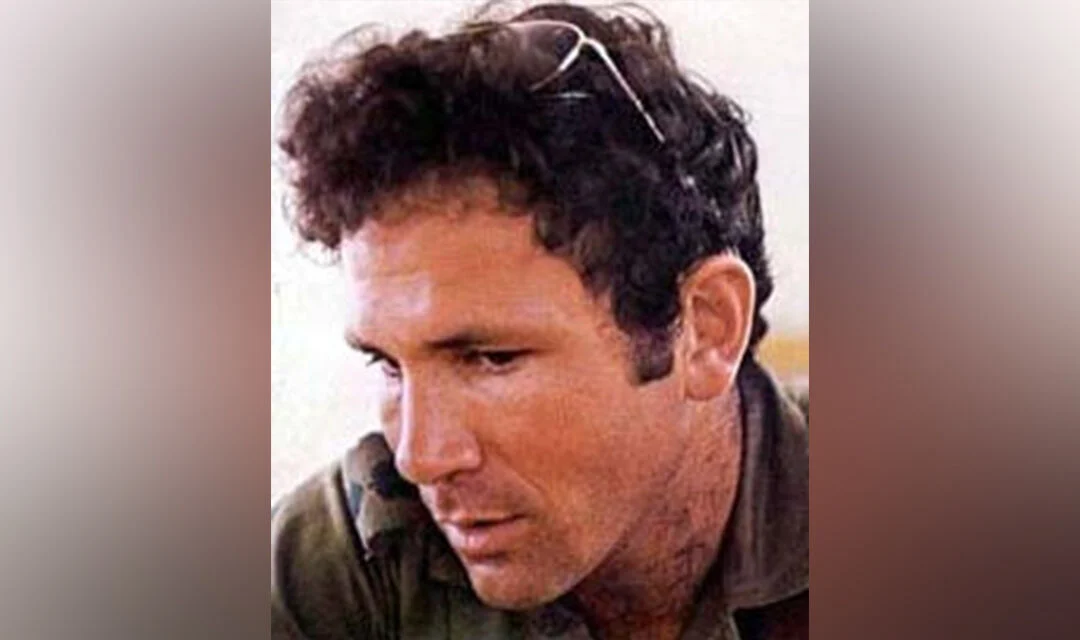

Thanks to that teaching, Rav Freilich became a rabbi at the age of 17. He lived and studied in Warsaw until he was deported to various labour and extermination camps.

He was in Auschwitz when, on the path that would have led to his death, the SS miraculously said they needed blacksmiths and, although he knew nothing of that craft, he volunteered and managed to save himself. He was moved to Mauthausen and then, towards the end, to Bergen-Belsen, where he was liberated by the Jewish-British brigade in 1945, on a Friday in May.

The soldiers asked if anyone knew English, no one answered, then they asked if anyone knew Hebrew, and he stepped forward. The soldiers offered to take him to the military camp to wash him, give him clean clothes and feed him.

“For many years I have not observed Shabbat, I have not been able to do it because I had to survive, work to be able to live, but now I am free and I can observe it. I’ll wait until sunset to get into that car”, Elie, in the grip of emotion, recalls the words of his grandfather on the day of liberation.

One soldier was very impressed by those words with which the Rabbi described all the drama of what he had experienced, but also his great love for Judaism, so much so that he returned to pick him up the following Sunday.

It was the same soldier who asked him what his plans were: “My father wanted to go to Israel. The soldier told him that he would try to organize his transfer to Salzburg where they were organizing an illegal Alyah. He failed to get to Austria. They moved a lot of Jews on trains to Italy so he decided to go to Rome. – his son Avi tells us – he managed to catch a train, despite the fact that he didn’t have a penny in his pocket. Arriving in Rome he was surprised to see that there were many people at the station. Those people had learned that the Jews who had survived the camps were returning on those trains”. And in fact everyone was waiting for the return of a loved one of whom they had heard no news.

When Rav Freilich arrived in Rome he did not know anyone, he did not know the city, he had nothing with him, so he decided to approach a person, the only words with which he was able to make himself understood were “Sinagoga! Sinagoga!”. The latter, realizing that he was a foreign Jew, drove him to the Tempio Maggiore where he was directed to the DELASEM (Delegation for the Assistance of Jewish Emigrants).

Rav Freilich hoped to find someone who could communicate with him perhaps in Yiddish or Hebrew and wanted to meet the Chief Rabbi of Rome, because as Avi tells us “it was tradition that the first greeting was for the Chief Rabbi of the place”, but the capital yet e did not have one because the last one had decided to convert, subsequently Rav David Prato was appointed and with him he forged a strong bond.

At DELASEM, in the light of the forms he had filled out, they realised that he had studied at the Yeshivah in Warsaw, that he knew Yiddish, so they asked him to stay. In Rome he had various assignments, in particular that of being the point of reference for all non-Italian Jews.

Immediately after the war, between 25,000 and 30,000 Jews passed through the capital, while the Army was concerned with providing them with accommodation and food, Rav Freilich helped them with their religious needs, such as celebrating weddings, as documented by the records kept in the Historical Archives of the Jewish Community of Rome.

“My father had to make sure that the people he married were really Jewish and that they could get married. For example that they were not related to each other, or that they were truly unwed. It was not an easy job because he didn’t have many people to ask, I know he often wrote to Rabbi David Kahana of Jerusalem for cases that were not clear”, -Avi tells us. “He was assigned to the Temple in Via Balbo, and was very proud to have contributed to its reopening after the war and forged a very strong friendship with Rav Prato, the person active in reorganizing the community”.

The rabbinic college was not functioning at that time and he was asked to restore it, so he reopened the Yeshivah, he also started teaching and giving lessons in kashrut.

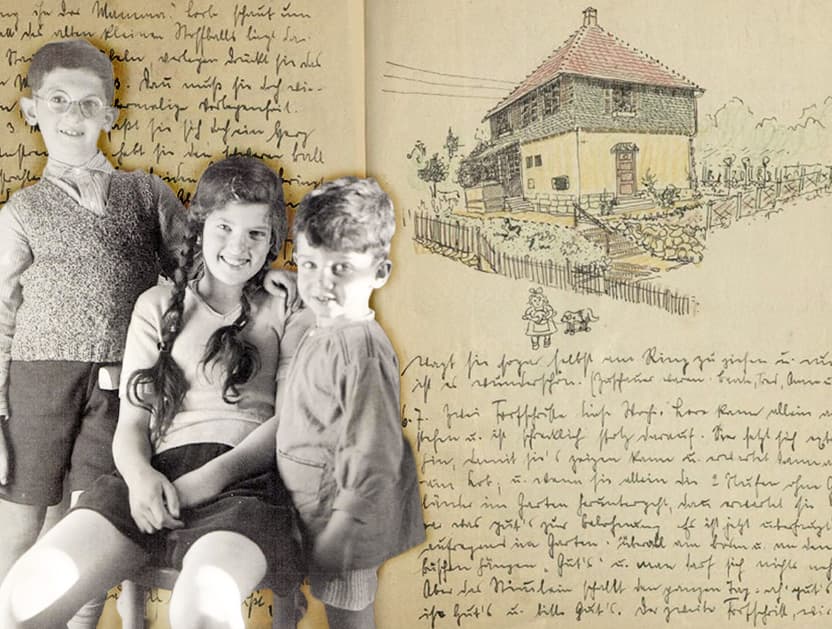

Rav Freilich organized meetings with teachers in Milan for the Jewish education of some orphaned children, and was impressed by one woman in particular. He asked her to become his personal secretary once he returned to Rome. That woman became his wife three months later and the wedding, as the photos show, was celebrated at the Tempio Maggiore in Rome.

Thanks to his wife he decided to move. “My grandmother said that the future of the Jews was in Israel or the United States, so they decided to leave thanks to a permit obtained through a New York rabbi,” Elie tells us.

At first Rav Prato did not like the news: “He got very angry. My father often told me about the day of his departure. Rav Prato told him that the time had come. They never lost sight of each other, they always remained excellent friends until Prato’s death a few years later ”.

However, Rav Freilich remained very attached to Rome, even after his departure he felt that the city and the Roman Jews had given him a new lease of life, they had welcomed him and he never forgot what they had done for him. He was the right person, in that place, at that time: he knew Hebrew, he taught it as Rav Shapira had taught him, he knew how to communicate and be close to people whether they were observant or not. He contributed to the rebirth of the Jewish community of Rome.