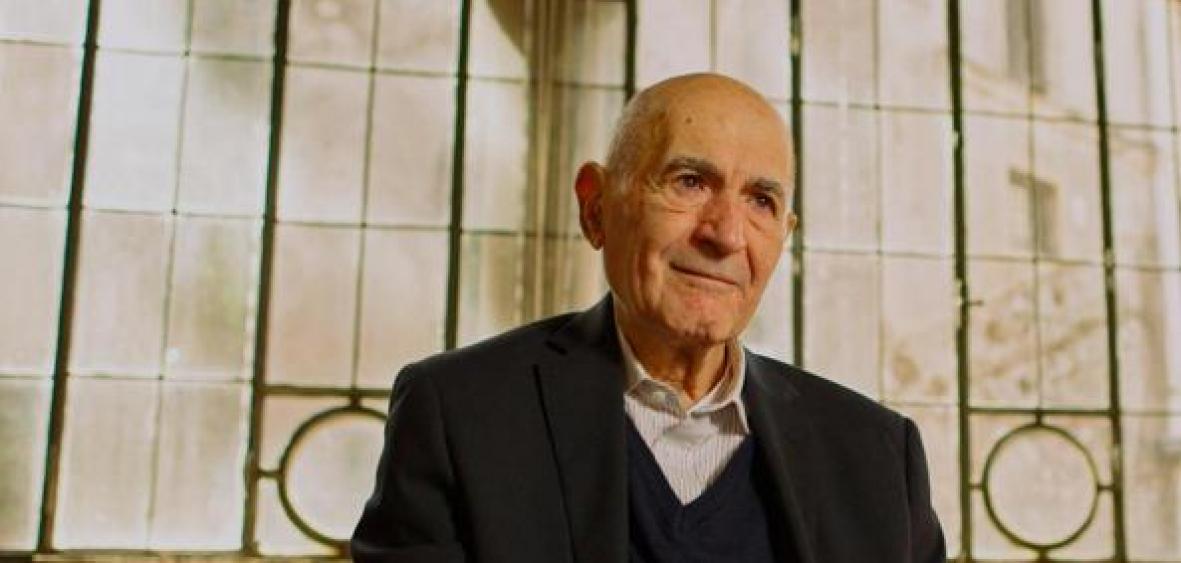

We publish below some extracts from the contribution of the Director of the Jewish Museum of Rome Daniela Di Castro Z”L taken from the catalog of the exhibition “Et Ecce Gaudium – “, The Jews of Rome and the Solemn Possession Ceremonies of the popes” – An essay by Daniela Di Castro Z”L- set up on the occasion of the visit of Benedict XVI at the Major Synagogue in January 2010.

“Desirous, His Holiness of Our Lord, Pope BENEDICT XIV, happily Reigning, 8 months and 13 days after he was deservingly raised to his sublime state and incomparable rank of Vicar of Christ on Earth, to gratify the public longing to see him take possession of the Holy Basilica of St. John Lateran, in solemn procession, and not of only the aforementioned but of the Holy Principality of the entire Church, sitting in this Holy Roman See, established the day of Sunday, the 30th of April to carry out this ceremony, which was followed, as we will relate, to the indescribable solace of his beloved Subjects, and the admiration of peo-ples even from afar, who assembled at this solemn event, one and all trusting in a long period of happi-ness under his not less glorious than greatly loved Rule”

Thus, on May 6, 1741, the Diario Ordinario by Chracas, a newssheet printed in Rome, described the preparations for the papal “Solemn Possession”, to which the Jews were also required to contribute. Papal Possession was the last act of the ceremonies carried out upon the election of a new pontiff, after the Conclave and the Coronation. With this ritual, as Bishop of Rome, the pope left his residence – the Vatican and, generally after 1724, the Quirinal Palace – and went for his investiture in his cathedral, St. John Lateran. Atthe same time, as temporal sovereign, he rode horseback in the midst of an opulent procession through ancient and monumental Rome, taking possession of the City in a rite of passage and of auspicious hopes for the future, in which the history of Rome and its ancient splendor were joined with those of Christianity, with particular reference to Constantine who had built the two basilicas united by the procession. During the Middle Ages, the taking of possession of the city by the pontiff, Vicar of Christ, was likened to the entry of Jesus in Jerusalem.1 In addition, the procession route in that period at times also had violent undertones and was a sometimes bloody seizure of power. It was a ritual fraught with danger, becauserival factions attempted to block the pontiff with the intention of invaliding his ascent to the throne. During the Renaissance, the ceremony took the form of a Christian renewal of the triumphs of the Roman emperors, while during the Baroque period and in the Eighteenth Century much more pomp was added to these meanings, with a great use of “ephemeral displays”, ornamentation constructed of wood, papier-mâché, cardboard and other lowly materials planned to last only for the duration of the ceremony, but thatmade it possible to reconstruct or decorate the façades of buildings, arches of triumph and all sorts ofscenes. The effect was one of great magnificence, partly due to the fact that these decorations were often the work of distinguished architects and artists. In the Nineteenth Century, the pomp was gradually abandoned and radically simplified: the route was covered rapidly and almost privately, no longer on horse-back, but in a carriage. The Jews had been involved in the papal Possession ceremony since the Middle Ages. Even back then, theywere considered Roman citizens to all effects and purposes: their presence in the city has been documented as long ago as the 2nd Century BCE. For that reason, in every era, their inclusion was a fundamental credential for their legitimization within Roman society. That notwithstanding, the ritual meeting of the Jews and popes on occasion of Possession took the form defined by their relations. First, there was the fact that the pope was not only the spiritual head of Christianity, but also temporal sovereign and heir of the Roman emperors who had granted the Jews Roman citizenship. Then, there was the question of the “chosen people”, a Biblical definition of the Jews, which the Christians considered annulled in favor of the Christians, the “verus Israel”, since the Jews did not acknowledge Jesus as the Messiah. In this context, the Jews physically embodied the condition of error and blindness that Christianity was called on to benignly tolerate, but also to rectify.

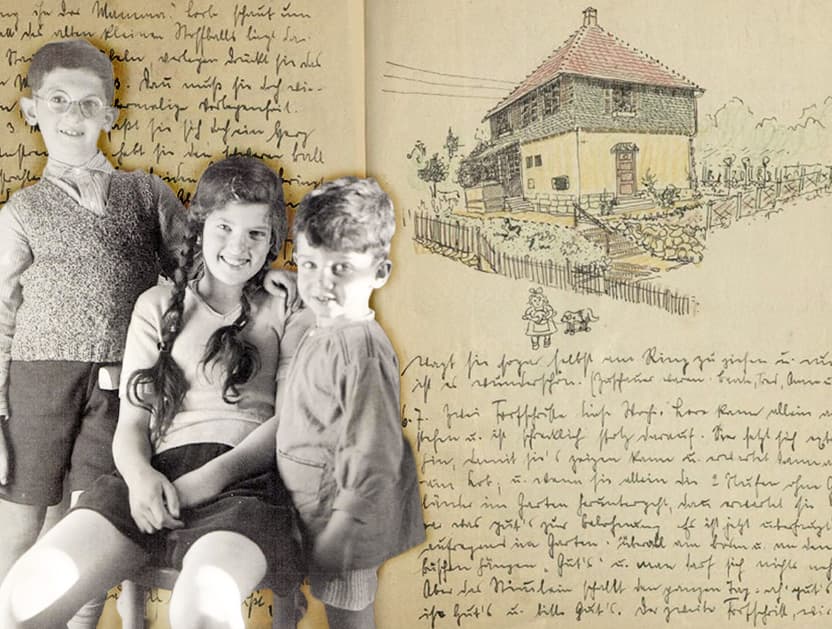

It should be underlined that the Jews’ participation in the Possession ceremonies took place within the framework of a rite where everything was codified, arranged and expected. It therefore channeled emotions but in a way that made them inoffensive. It was carried out according to a script with symbolism conceived to define and publicly declare the nature of the relations between the Pontiff and the Jews of Rome. The variation of the rite throughout the centuries gives an indication of how these relations changed. The first testimony of the Roman Jews acclaiming the election of a pope dates back to 1119 for Callixtus II. They played a special role, and celebrated the pope together with the Christians, while in 1111 they awaited the triumphal entrance of Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV as a separate group. In 1143, however, the investiture of Celestine II included a ritual that was destined to last until the beginning of the 16th Century, the rapraesentatio Legis, in which the Jews carried a Biblical scroll in front of the Pope as they sang sacred Laudes.4 The initial meaning of this rite was self-introduction: the Jews described themselves proudly as the “people of the Book”, loyal to the Pentateuch. The scroll was also carried in processions in honor of emperors, documented by a drawing depicted Henry VII in 1312, where the Jews carrying the scroll ofthe Bible – as portrayed by the Rhenish artist – wore a pointed head like the Jews in Germany, something which the Jews of Rome did not wear.5This statement of pride became a source of humiliation when the rite included an exchange of declarations between the Jews and the pontiff. The former asked him to confirm and approve the Law contained in the book, and the pope responded that he approved the Law but that the interpretation given by the Jews was futile and condemnable.6 In addition, the entire ritual had violent undertones given that, starting at least from Pope Gregory XII (1406), the Jews gave the scroll, covered in rich textiles, to the pope as a gift, and not simply to look at. In response, the pope accompanied his words of refusal with the ritual gesture of throwing the scroll to the ground. The ritual meeting between the pontiff and the Jews took place near the Parione Tower (but at Monte Giordano in 1447) before a crowd already excited by the coins that had been thrown to them. The possibility of getting hold of the Pentateuch adorned with precious textiles led to violent rights, which can well be defined as ritual sacking. As a result, starting with the Possession ceremony of Innocent VIII in 1484, the Jews were moved to a spot in front of Castel Sant’Angelo. This location was safer because it was fortified and a garrison was stationed there. It was built however on top of Hadrian’s Tomb and was therefore full of negative overtones for the Jews: it was with Hadrian that the Jews foughta bitter battle over his prohibition against circumcision. Bernard Picart engraved an illustration of the offering of the Bible scroll in 1725.8 The engraver had apparently never seen the ritual of rapraesentatio Legis, but he must have known about it from the sources and, perhaps believing that it was still being practiced during his times, he set it under an invented archwith something looking like the Coliseum in the background, more or less where in the Eighteenth Century the Jews paid homage to the newly elected pope. Instead, the last documentation we have of the Jews offering a Bible to the pope refers to the election of Leo X in 1513. “Confirmamus sed non consentimus” was this pope’s answer as well, dropping the scroll to the ground and continuing on his way. More than one person must have noticed the difference between this behaviour and that of his father, Lorenzo II, the Magnificent, whose court witnessed a blossoming of Jewish studies. It should be noted that Leo X showed the same interest, which confirms that the contemptuous response of the rapraesentatio Legis was a codified ritual, difficult to change. From this time on, however, the ritual gift of the Bible to the popes disappeared from the reports of the Possession ceremony. Throughout the Sixteenth Century, the position of the Jews of Rome rapidly worsened. The burning of the Talmud in 1553 was followed two years later by the establishment of the ghetto. The sources are silent on the role of the Jews until 1590, when – for the election of Gregory XIV – they were ordered to hang placards containingauspicious passages from the Bible in Hebrew with Latin translations under the Arch of Septimius Severus.This was a meaningful derivation from the tabulae pictae of the ancient Roman triumphal processions. The novelty of the placards with Hebrew passages was used again for the Possession ceremony of Innocent X in 1644, but this time, the Jews were assigned the part of the route from the Arch of Titus to the Coliseum. cious tapestries and textiles along the road from the Arch of Titus onwards continued until 1775. It was no accident that the Jews were assigned the section of the road after the Arch of Titus. The location was humiliating because it was in the shadow of a monument depicting the enslavement of the Jews after the destruction of the Sanctuary in Jerusalem. This was such a traumatic event that the Roman Jews avoided walking under it until today, or at least until the proclamation of the State of Israel in 1948. The Coliseum – the end of the section assigned to the Jews’ decorations – was also the site of infamous memories because it was believed to have been built with the booty from the Jewish Wars, using Jewish slaves as workers, even though the Church always emphasized the monument’s role as the stage for Christian martyrdom.

The selection of text extracts is curated by Michelle Zarfati