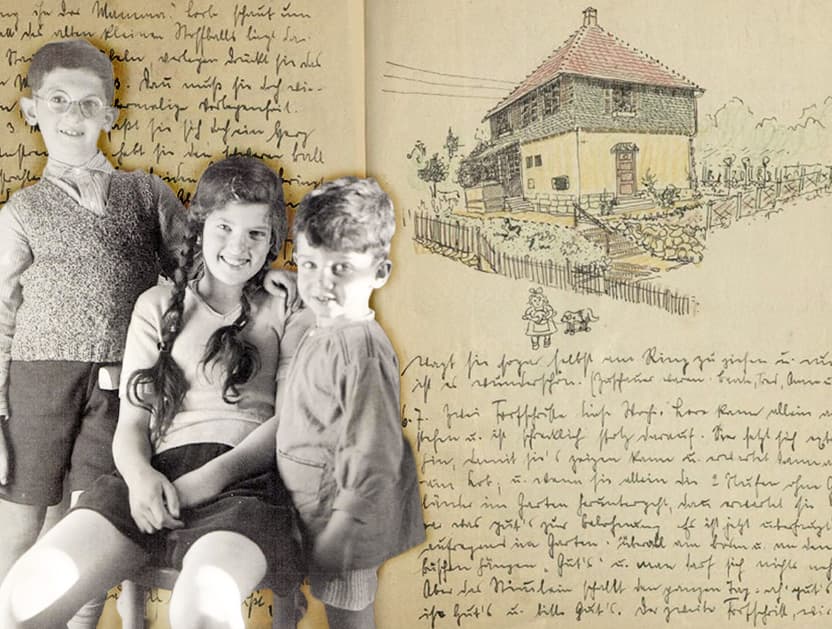

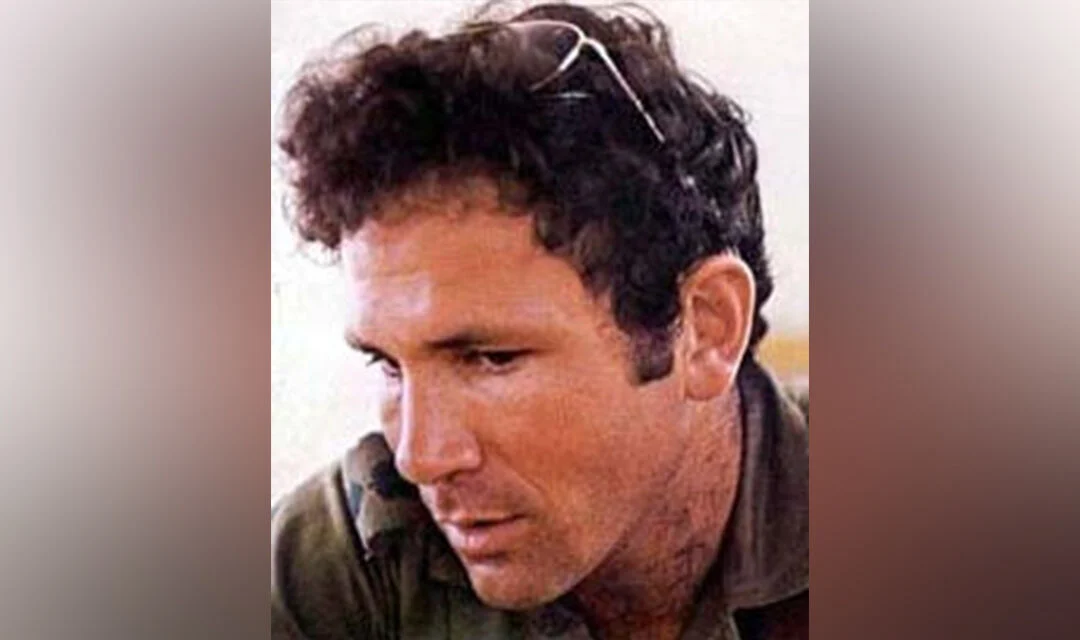

A picture, a phrase, even a dream can bring it back suddenly. After you experience a terrorist attack, the nightmare never leaves you: it keeps resurfacing in your life whenever it finds the smallest crack in your memory. Gadiel Gaj Taché’s never-ending nightmare of October 9, 1982—the day of the terrorist attack on Rome’s Synagogue—keeps coming back every day, it in the death of his younger brother Stefano, killed at age 2 in the attack perpetrated by Palestinian terrorists, and in the shrapnel from the grenade that exploded next to him and injured him forever. For many years, Gadiel never spoke of his private grief, never publicly denounced the inaction of the authorities that failed to protect the Jews of Rome that day, never indicted Italy for suppressing those memories still awaiting a truthful explanation. He kept quiet although the pain was there with him all the time, screaming silently, in every single moment of his life. Then the time came for Gadiel to talk about it. After a long gestation process, he has now written about it in Il silenzio che urla [Screaming Silence,] published by Giuntina in 2022. He has poured all his grief into this important book as into a journal intime; he has described all the stages in his personal experience, but has also chronicled in a direct language all the stages of this unsolved riddle as in an investigative account. Upon the publication of his book, Gadiel Gaj Taché agreed to be interviewed by Shalom.

SHALOM: Gadi, it was 2011 when you started talking about your experience of the Oct. 9, 1982 attack, and now your book has been published. How did you get there? Did the 40th anniversary prompt you to go public?

GGT: This book had a very long gestation. In a way, the idea has been going around in my mind for many years. In 2015, a few days after the Paris attacks, something clicked inside me. I felt I was on the front line in the fight against terrorism. I thought it my duty to get the story of the attack on Rome’s Synagogue out there, so that the Italian public would learn that international terrorism had already hit hard in our country. I realized that it was important for me to keep talking about my story, but more than that, it was imperative that I do something that could stick. Of course the original idea was very long in taking shape, and I had to work hard on myself before I could make the book happen.

SHALOM: What is striking about your book is the caution with which you deal with your emotions, with the account of the tragic attack and with the explanation of the events that led up to Oct. 9.

GGT: I tried to write this book as if it were a journal, as if I was talking to myself. I am no historian, nor am I a researcher or a writer. Therefore it was not easy to confront the events of that nefarious period, to deal with my emotions and to put it all down on paper. As I wrote, I tried to measure out my emotions as best I could; I tried to be as rational as possible in order to come up with a detached account.

SHALOM: In recent years you have been researching the history of that period and trying to trace the many events related to the Synagogue bombing. In this quest for the truth, you have learned many things you never knew about that attack. Is there a detail, a document, a fact you can share with us that came as a revelation or as a confirmation of what you knew?

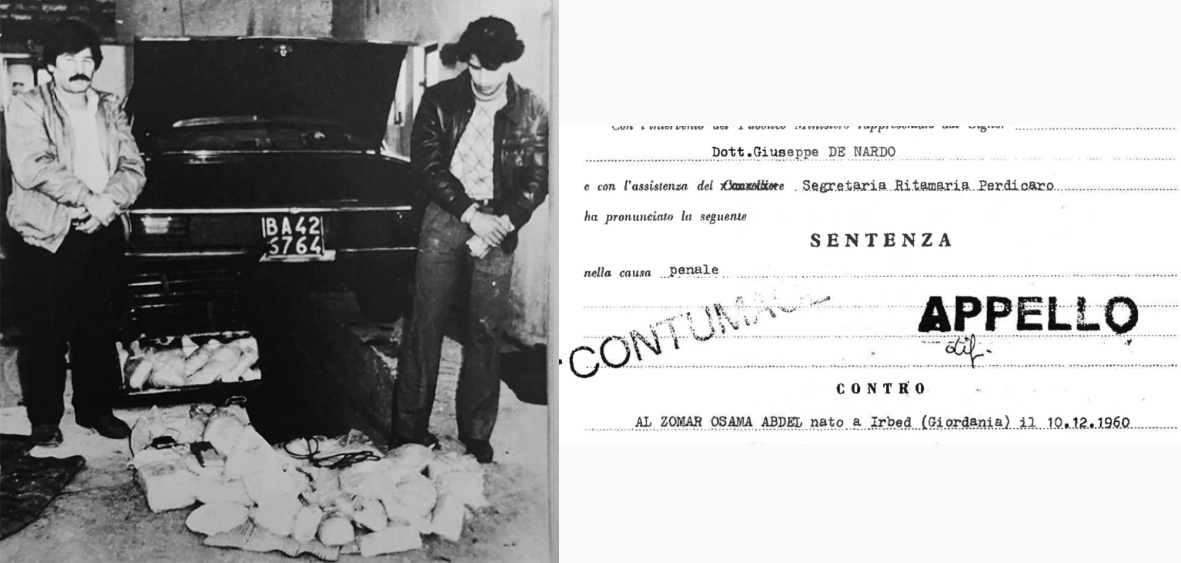

GGT: In the documents I had a chance to consult at the Central State Archives I found a wealth of information that struck me. For example, I found as many as 17 warnings issued by Italy’s secret services between June and September 1982 concerning the imminent danger of attacks against Jewish and Israeli targets. One of these alerts even listed Jewish gathering places that might be at risk. They included schools, community centers and synagogues. Thus I came to realize that the Italian authorities were not unaware of the threats against a substantial number of citizens. I also found an early statement by the former girlfriend of Al Zomar (the only person indicted for the terrorist attack, who was sentenced to life imprisonment in absentia by the Italian judges.) Soon after her boyfriend’s arrest, the young woman declared that he had confessed to her that he had been among the perpetrators, and that he had received the order from the PLO. This document struck me most of all: I had always known that the instigator of the Synagogue bombing was Abu Nidal, the leader of a Palestinian faction believed to be in opposition to Arafat’s PLO. But I was startled upon finding out about Al Zomar’s confession such a long time after the events.

SHALOM: You have often told me that your felt an urge to hand down your memories of Oct. 9, 1982 to young people. As I read your book, I noticed that in addition to sharing with the public an important testimony that all Italians should read if they are to understand that period of our country’s history, you have crafted a knowledge tool for young people and students. Is that the goal you pursued?

GGT: Young people were always my primary focus: they are our future, and they will have to preserve and hand down the memory of those events. My family and I have always dreamed that this important event in Italy’s history would be studied in schools. Thus, my intention and hope was just that: to offer young Italians a simple and effective tool that would help them understand this story in depth.

SHALOM: What, if anything, has changed in these four decades about the memory of Oct. 9, 1982?

GGT: For many years recollections of that attack were somewhat sidelined. I think that Italian society has viewed this story as someone else’s tragedy for much too long—as if those events had affected Jews only. But in recent years, especially after President Sergio Mattarella’s inaugural address for his first 7-year term, the story of the terrorist attack on Rome’s Synagogue has gained greater attention by the mass media and the public. Much is still to be done, but I think we are on the right track to shed full light onto those events.

SHALOM: Will you continue your quest for the truth? And do you think that this can help to do justice?

Surely, the truth should always be sought, and I hope my book can bring this matter back to the attention of Italian society. But as far as doing justice is concerned, I don’t expect it to be done. Forty years have gone by since those events—years of unanswered questions, for example regarding the reason why the Synagogue failed to be put under adequate surveillance on Oct. 9, 1982. Yet if we give up seeking the truth and demanding justice, it would be a defeat for all of us and for Italy as a whole.